Analytical Model for GPU Kernel Performance Prediction

with high accuracy for both linear and non-linear time functions

Abstract

With the deceleration of Moore’s Law and the attenuated progress in hardware technology, the imperative now lies in the development of efficient and parallel software to mitigate the scarcity in hardware capabilities. In recent years, the demand for processing vast amounts of data across diverse domains has attained paramount significance. A considerable focus has been directed towards advancements in Machine Learning and Deep Learning, necessitating intensive data computations. Simultaneously, the scientific domain has experienced a substantial surge in data collection methodologies, precipitating a necessity for intricate data calculations. Consequently, there has been an exponential surge in the utilization and evolution of Graphics Processing Units (GPUs).

While Central Processing Units (CPUs) were hitherto the benchmark for diverse computations, their inherent limitations in handling massive parallel applications have paved the way for General Purpose GPUs (GPGPUs). GPU applications are now pervasive and find application across various domains, yielding unprecedented performance enhancements and significant cost reductions due to GPUs’ superior power efficiency per computation compared to CPUs.

Nevertheless, the development of GPU code is a non-trivial undertaking. Software developers, accustomed to learning algorithms and general software development in a sequential manner, must invest time and effort in transitioning to parallel thinking. Consequently, planning and developing massively parallel GPU code entail substantial cost implications. Furthermore, GPUs are applicable only to specific problem types that exhibit notable characteristics conducive to parallelization.

Identifying a problem suitable for GPU utilization raises questions regarding the potential performance improvement compared to traditional CPU execution without parallelism. Thus, predicting the performance of GPU code (analogous to kernels on GPUs) becomes crucial in quantifying potential enhancements resulting from the parallelization of software for GPUs. This report introduces an analytical model designed to predict the execution times of GPU kernels for unknown problem sizes without actual execution. The model considers various metrics involved in launching kernels, including problem size, block size, and grid size configurations, enabling the prediction of expected execution times. It is also shown that the prediction can be extended to different GPUs, considering their own hardware characteristics. Consequently, the model instills a degree of confidence without necessitating an in-depth understanding of kernel intricacies, their functionality, or how they scale with increasing problem sizes. The model automates this process, providing a streamlined approach to performance prediction. For the simplicity of the model, it offers adequate prediction accuracy and provides good scope for future expansion to consider more niche parameters affecting all kinds of kernels and subsequently their performance.

The Analytical Model

The analytical model is primarily based on counting the number of instructions and determining their nature and how much they contribute to the overall execution time. This simple yet effective metric forms the crux of the whole execution time calculation.

It is possible to extract the total number of computational instructions present in a kernel code. These simply constitute the non-memory transactional instructions. For example, floating point additions, subtractions, divisions and so on. Every type of instruction carries with itself a certain weight, in this case it is simply the total number of cycles these standard instructions would take to finish execution. For example, from literature, through the use of micro-benchmarking it can be seen that Fused Multiply Add (FMAs), additions, multiplications, divisions take approximately 2, 24, 32, and up to 96 clock cycles (Mei et al. [9]). These values will be used as weights when summing together the total cycles required for computational instructions.

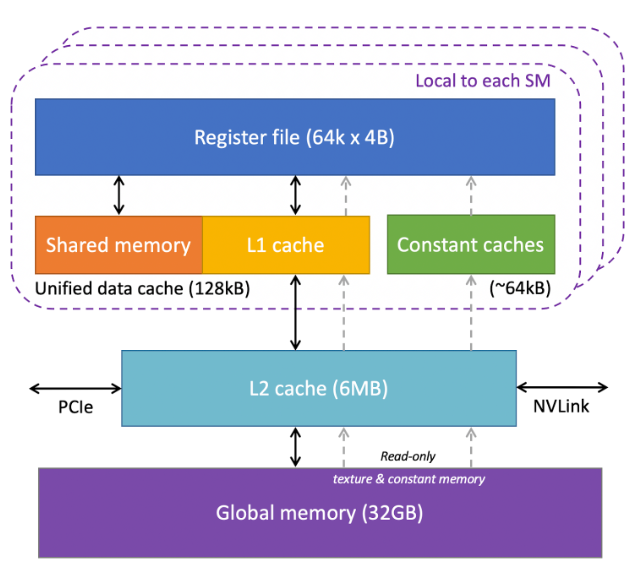

Another basic type of instructions contributing to the execution times are the memory transactions. These could be either load or store instructions. Since we have to deal with a multi-layer memory hierarchy as discussed earlier, we have to be wary of the fact that the type of memory differentiates the total number of cycles it would take to perform a memory transaction with the said memory. It is known that accessing global memory is around 100x times slower than accessing the shared memory (or L1 cache since they share the same hardware). Therefore for the simulations, it can be considered that accessing shared memory takes around 5 cycles compared to 500 cycles that would be required for accessing the global memory. Similarly it can be considered for the L2 cache, which lies in between L1 cache/ Shared memory and the Global memory in the memory hierarchy that it would take around 250 cycles for memory transactions on it.

These instructions can very well be automatically detected using a kernel code parser. But for the sake of simplicity of the project, these values were determined by hand by simply perusing through the kernel code for multiple different kernels.

Let ncomputations be the number of computations as calculated by hand. Let memAccessGM be the total clock cycles taken by global memory accesses and memAccessSM be the total clock cycles taken by shared memory accesses. If we were not to consider the caches, we have:

- memAccessGM = (loadsGM + storesGM) * latencyGM

- memAccessSM = (loadsSM + storesSM) * latencySM

We could disable caches during compilation and the above equations would suffice in such a case. If we had to consider the effect of caches, then we would have to slightly modify the above equation as follows:

- memAccessGM = (loadsGM + storesGM - L1hits - L2hits) * latencyGM + L1hits * latencyL1 + L2hits * latencyL2

Where the loads and stores are those as calculated by hand and the latency values are as mentioned earlier in the section.

Similarly if Nthreads is the total number of threads spawned as the kernel is launched, F is the processor clock frequency and O is the occupancy and adjustingWeight denote a value which accounts for other parameters influencing the total execution time, then we can denote the total execution time as below:

- E.Ttotal = Nthreads * (ncomputations + memAccessGM + memAccessSM) / (F * O * adjustingWeight)

Where occupancy O is determined by the compute capability, block size, register usage and shared memory usage as described earlier.

The adjustingWeight is catering to all the additional parameters and weights that haven’t been considered in the equation but previously discussed. These include divergences, uncoalesced vs coalesced memory accesses, bank conflicts, etc. This parameter is calculated as the ratio of estimated execution time to the actual execution time. This is only calculated once by executing the kernel for some arbitrary input size. However this parameter can serve for other input sizes and we wouldn’t need to execute the kernel for such instances. This behaves as a scaling factor in addition to the other parameters defined as part of equation 4. This is quite effective when we observe that execution times scale with increasing input sizes. The parameter remains constant and doesn’t change for that specific GPU and problem statement, but it changes for different kernels and different GPUs. Note that this parameter alone wouldn’t suffice since the correlation of execution times to the input size is not always simple. The understanding of other contributing factors such as both memory and non-memory computations and occupancy provide the necessary modeling to accurately determine the execution times.

It is important to note that this analytical model can be used on any GPU platform. The only things changing would be the hardware characteristics of the GPU, which may change the latency values and clock rate, but the primary scaling factors depend on the nature of the algorithm. The constants which determine the actual execution time is just taken into account by the adjusting factor. Therefore for simplicity, experimentation has been performed on a single GPU across 4 different kernels of unique computations, to show a metric for accuracy.

Results

Aggregating results from the experiments, we have the following:

| Error Metric | Matrix Vector Multiplication | Dot Product | Vector Addition | Matrix Addition |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Absolute Error (MAE) (in ms) | 16.37 | 58.18 | 8.28 | 6.96 |

| Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE) (in ms^2) | 24.92 | 78.09 | 11.96 | 8.73 |

| Deviation (in percentage) | 3.51 | 8.74 | 5.03 | 10.3 |

Combining all results, it can be seen that the percentage deviation of the predicted execution times with respect to the actual execution times comes under 6.9%. This error creeps in due to the nondeterministic nature of the actual execution times itself, where a lot of dynamic parameters are at play. However, for the simplicity of the model, it provides a good estimate. This can be very well extended to more kernels and across different GPU systems.